Is Gov. Baker’s Special Panel Evaluating the MBTA Fairly?

April 7, 2015

Frontier Group | Tony Dutzik | 04/07/2015

As Gov. Baker’s special panel on the MBTA prepares to release its recommendations for the future of transit in the Boston area, it is important that its conclusions be based on accurate information. Writing in CommonWealth yesterday, former state Transportation Secretary James Aloisi raised important questions about the statistics in a leaked version of the panel’s draft report.

As Gov. Baker’s special panel on the MBTA prepares to release its recommendations for the future of transit in the Boston area, it is important that its conclusions be based on accurate information. Writing in CommonWealth yesterday, former state Transportation Secretary James Aloisi raised important questions about the statistics in a leaked version of the panel’s draft report.

According to the Globe’s David Scharfenberg:

The report, in its latest iteration, is a slide presentation in silver and blue, filled with bullet points and charts on all manner of subjects. One reviewed by the Globe showed passenger fares cover a relatively small share of the MBTA’s operating expenses — 39 percent — compared with cities such as Chicago (44 percent), San Francisco (76 percent), and London (90 percent for its subway system alone).

In his piece for CommonWealth, Aloisi found that those numbers “don’t stand scrutiny.” He points to an issue that we’ve discussed at length: the difficulty of developing accurate comparisons between the MBTA – which offers a complete menu of public transportation services on both the regional and local scale – and transit agencies that offer only some of those services.

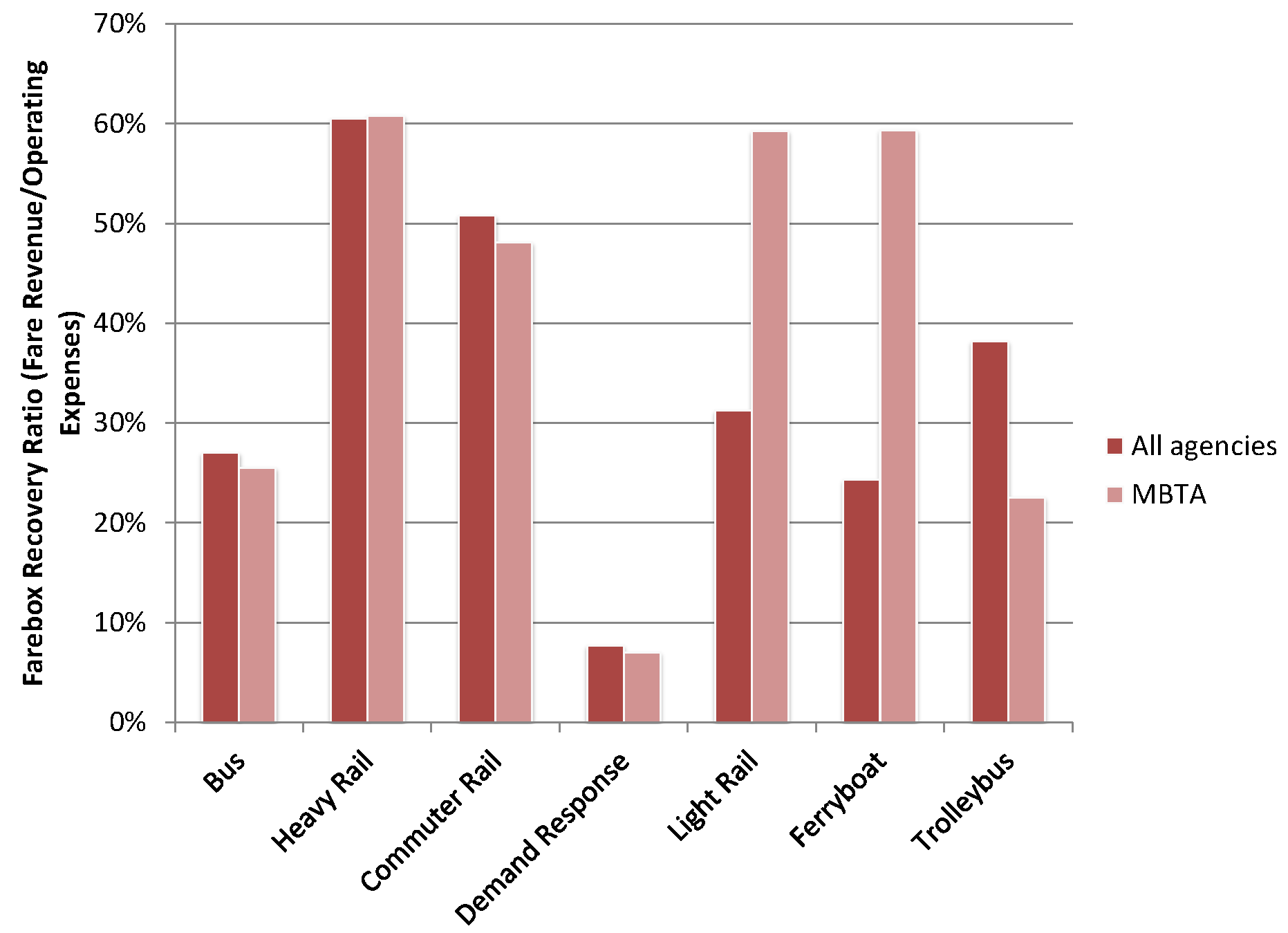

The most accurate way to compare the MBTA’s “farebox recovery ratio” – the percentage of operating expenses that are covered by passenger fares – with those of other agencies is to compare those figures on a mode-by-mode basis. In other words, we should compare the ratio for bus vs. bus, train vs. train, etc. We’ve used 2013 data from the National Transit Database to do so, and will present the results below.

Before we do, though, it is important to understand why the MBTA’s farebox recovery ratio matters – and why it doesn’t. Simply put, farebox recovery measures the share of the cost of a service that is paid for by those who use it. If more of an agency’s operating cost is covered by riders, taxpayers need to spend less to keep the service running. All other things being equal, that’s a good thing.

But there are many times when it makes sense to spend more, rather than less, to subsidize transit service. If transit subsidies can address a transportation need at lower public expense than the available alternatives (e.g., adding another lane to the Big Dig), if they can deliver public benefits that exceed the costs (e.g., reducing air pollution or curbing congestion), or if they can meet a pressing and vital societal need (e.g., providing mobility to the disabled), a low farebox recovery ratio may be perfectly acceptable.

Now back to the data. The chart below compares the farebox recovery performance of the MBTA with the national average for each mode of transit, according to 2013 data from the National Transit Database.[1]

Figure 1. Farebox Recovery Ratios: MBTA vs. National Average, by Mode

Two things stand out about the data:

- For the major modes of transit the MBTA provides – heavy rail (subway), light rail (Green Line), bus and commuter rail – the MBTA’s farebox recovery ratio is comparable with those of other systems nationally, outperforming the national average in two cases (light rail and heavy rail) and slightly underperforming in two cases (bus and commuter rail). In every case but light rail (for which the MBTA’s farebox recovery ratio is the highest in the U.S.), the MBTA’s ratio is within a few percentage points of the national average.

- The farebox recovery ratios of different transit modes vary widely. Demand response paratransit service, for example, never comes close to covering its costs with fare revenues. Yet few would argue that we realistically could – or should – charge the elderly and disabled the same share of the cost of their transit services as other users. Transit systems that do not offer bus or demand response service often look “better” than systems that do offer those services when compared on the basis of farebox recovery alone. It is important to keep that in mind when comparing the T with other agencies.

All of this points to two arguments we’ve made repeatedly, in this space and elsewhere:

- When compared fairly and accurately on most measures (as previously reported in the Globe), the MBTA often falls in the middle of the pack among U.S. transit agencies. It neither excels in measures of cost-effectiveness or efficiency across the board, nor does it consistently lag behind. As Massachusetts residents, we should not settle for “average,” and the MBTA and the special panel should look to emulate agencies that deliver specific services particularly well. But the MBTA’s performance versus other agencies suggests that improving the agency’s efficiency – while desirable – is not going to be nearly enough to solve the agency’s massive, systemic problems.

- When it comes to transit, as a Commonwealth, we generally get what we pay for. Increasing the share of transit expenditures covered by riders could play a small role in addressing the T’s financial woes, but doing so may reduce the number of people choosing to ride transit. This would set us back in other ways – by putting more cars on the road, hampering economic development in our cities, or increasing the burden of transportation costs on those least able to pay them.

As Gov. Baker and the Legislature prepare to make important decisions about the future of the MBTA, it is critical that the information they use be accurate and presented in a context in which its implications can be fully appreciated. Let’s hope that the special panel’s final report fulfills that promise.

[1] For this chart, farebox recovery ratio was calculated by comparing fare revenue with operating expenses for each mode, with data sourced from the NTD’s National Transit Profile Summary for All Agencies and the MBTA’s NTD Transit Profile.

Recent Comments